Brief Introduction to the Bash Shell

Overview

Teaching: 0 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

What is the Bash shell?

How do I use the shell to run programs?

How do I navigate the file system using the shell?

Objectives

Explain the purposes of the shell and a terminal, and the differences between them.

List some key benefits of using the shell as opposed to a graphical user interface.

Use a terminal to access the shell to run commands and programs.

Use the shell to navigate around the file system and manipulate files.

Before we venture into Python, we need to take a look at the Bash shell, which is one way of running programs on a computer. Throughout this course we’ll be using the Bash shell a great deal, and it’s arguably an invaluable tool for anyone looking to write software: it can give you greater control over your computer’s functions and in many circumstances operations are more efficient using a shell-type interface - particularly for repeating sequences of actions multiple times.

What is the Bash Shell?

The most common way users interact with their computers today is via Graphical User Interfaces, or GUIs for short, such as those present in Microsoft Windows or Mac OS. However, before these came along it was typical to feed instructions to computers purely via the keyboard, into a command line interface, or CLI for short: commands are typed in, executed by the computer, and output from those commands displayed to the user, with this cycle constantly repeating.

This description makes it sound as though the user sends commands directly to the computer, and the computer sends output directly to the user. In fact, there is usually a program in between called a command shell. What the user types goes into the shell, which then figures out what commands to run and orders the computer to execute them. Note, the shell is called the shell because it encloses the operating system in order to hide some of its complexity and make it simpler to interact with.

One of the most prevalent ones, the Bash shell, has been around longer than most of its users have been alive. It has survived so long because it’s a power tool that allows people to do complex things with just a few keystrokes. It also helps them combine existing programs in new ways and automate repetitive tasks so that they don’t have to type the same things over and over again. Use of the shell is fundamental to using a wide range of other powerful tools and computing resources (including “high-performance computing” supercomputers).

Running the Shell

Let’s start by running the shell. Programs that give you access to a shell are often called a terminal. If you’re using the provided SABS virtual machine (VM) or a provisioned laptop which uses Ubuntu, open a new terminal by right-clicking on the desktop and selecting Open in Terminal. You’ll be presented with a new window and something like the following:

dtcse@dtcse-VirtualBox:~/Desktop$

This is the command prompt, which awaits your typed-in commands (which will likely vary if you’re not using a SABS VM or laptop, but may contain some of these elements):

dtcserepresents your username you logged in asdtcse-VirtualBoxrepresents the name of this virtual machine~/Desktopis the folder - or directory in Linux speak - you are currently in, showing where you currently are on the file system. We’ll look into this a bit later

From here, you can type in and execute commands and see their output. For example, if you type the following and press Enter, it should show you your username:

whoami

And you should see:

dtcse

So here, we are seeing the fundamentals of the command line in action: type a command, have it executed, and then show us some output from that command.

Navigating the File System

A key aspect of any operating system is how it organises, stores, and retrieves its data. This is typically within a hierarchical arrangement of containers (folders/directories) which contain files - this arrangement is referred to as a file system.

Something that is often confusing about the shell is where and how you access files, and how this is all represented within the shell. One key thing to remember is that in the shell, you are always looking at somewhere in your hierarchical file system. This location is known as the working directory, and commands you run in the shell take this into account - it is the directory that the computer assumes we want to run commands in unless we explicitly specify something else.

One thing that tells us where we are is the prompt, which tells us we are at ~/Desktop - the ~ is a shell shorthand that refers to our account’s home directory, and Desktop is a directory within our home directory. Now within the SABS Ubuntu VM or provisioned laptops, our home directory is located at /home/dtcse. So, in fact, we are currently located at /home/dtcse/Desktop (if we replace the ~ shorthand).

Another way to find out where we are is the following - which stands for “print working directory” - and will output the current working directory in your shell:

pwd

/home/dtcse/Desktop

So similarly, this tells us we are in the Desktop directory, which is within our home directory at /home/dtcse. We can also see what’s in this directory by using ls, which is short for “list”:

ls

And we should see that nothing is printed, and the shell unceremoniously returns us to the prompt! This is because there is nothing in the Desktop directory, so nothing is printed. This is fairly typical of shell commands: when nothing needs to be reported - or if the command is successful - nothing is printed.

So let’s take a look at a slightly more interesting directory. We can change which directory we’re looking at - our working directory - by using the cd (change directory) command, and then take a look at what’s there. Let’s say we wanted to see what is in our home directory, i.e. /home/dtcse, which is the directory above this one. We could type the following, which brings us up one directory:

cd ..

Here, we’re passing an argument to the cd command. The .. argument here means “the directory above”. Again, note there is no output - the command was successful and had nothing to report.

We can check our working directory using pwd as before:

pwd

/home/dtcse

And typing ls now, we should see something like (which may look different on other systems):

Desktop Documents Downloads Music Pictures Public snap Templates Videos

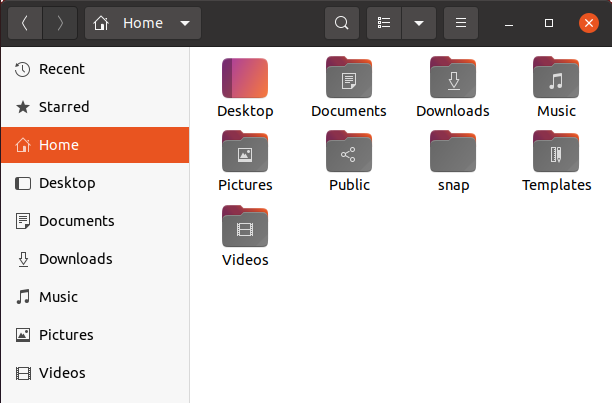

Another way to think about this is that it’s very similar to how a file explorer or viewer application shows you files. If you click on the folder-type icon in the sidebar on the left for example, you should see the following (although the colours may be slightly different):

Which in this case, indicates the files present in the /home/dtcse directory. Now, we can use the interface in a graphical way to move around and view the file system, which in a nutshell, is equivalent to using the cd and ls commands.

We can also pass special arguments to commands which change its behaviour, called flags. These flags are typically prefixed with a -. For example, if we use the -F flag with ls, it will show us the type of each entry shown (e.g. which are files and which are directories):

ls -F

Desktop/ Downloads/ Pictures/ snap/ Videos/

Documents/ Music/ Public/ Templates/

A following / indicates a directory - so, in this case, these are all directories! Note that whilst some flags are present and have the same behaviour between commands, by and large this is not a rule. Different commands have different behaviours and purposes, so have different flags to control their behaviour.

Now if we want to go back into the Desktop directory (a subdirectory of our home directory), we can pass it as an argument:

cd Desktop

So far, we’ve been moving around using relative directory designations, either moving from our current directory to a directory above, or moving down into a subdirectory. But we can also move to other directories with an absolute directory reference. To get to our home directory regardless of our current working directory, for example:

cd /home/dtcse

Other commands that reference directories - and files - operate the same way, as we’ll see later. ls /home/dtcse for example would show us the contents in that specified directory, again regardless of our current working directory.

Manipulating Files

We can also change things on the file system using various commands. To illustrate, let’s create a file to play with first in your home directory. We can use the touch command to create an empty file for us:

cd

touch test.txt

ls -F

Note here we didn’t pass any argument to cd at all, in which case cd will put us in our home directory. We should see something like:

Desktop/ Downloads/ Pictures/ snap/ test.txt

Documents/ Music/ Public/ Templates/ Videos/

We can copy files using cp (short for copy):

cp test.txt test2.txt

ls

Desktop/ Downloads/ Pictures/ snap/ test2.txt Videos/

Documents/ Music/ Public/ Templates/ test.txt

And we can move files using mv (short for “move”), e.g. into the Documents directory (or another of your choosing):

mv test2.txt Documents

ls -F Documents

test2.txt

Another feature of mv is that we can use it to rename files:

mv Documents/test2.txt Documents/file.txt

So here, we reference the test2.txt file we want to rename in the Documents directory by specifying the directory first.

We can also delete files using rm (short for “remove”). Warning: many versions of Linux, including this one, will not prompt for confirmation of the deletion first: the file will be immediately deleted. Plus, once you delete a file using this method, note the file will not be retrievable. This is unlike other graphical methods of deleting files with a file explorer, where they often end up in a “trash” folder where they can be “undeleted”.

rm test.txt

rm Documents/file.txt

Which puts our file system back into the state we first found it!

Getting Help

You can get help on commands in the shell by using the manual pages, or man pages for short, e.g.

man ls

Which in this case, will give you help on the ls command:

LS(1) User Commands LS(1)

NAME

ls - list directory contents

SYNOPSIS

ls [OPTION]... [FILE]...

DESCRIPTION

List information about the FILEs (the current directory by default).

Sort entries alphabetically if none of -cftuvSUX nor --sort is speci‐

fied.

Mandatory arguments to long options are mandatory for short options

too.

-a, --all

do not ignore entries starting with .

-A, --almost-all

do not list implied . and ..

...

Here, you can use the up or down arrow keys to scroll the text a line at a time, or the space bar and b key to move forward or backwards a page at a time. To exit this view, press the q key to quit back to the command prompt.

As a reference it’s a very useful and commonly used feature, since as well as a synopsis of a given command it gives you descriptions of the command’s arguments and flags and what they do - the core of the shell!

Other Shell Resources

Here are some resources you may find useful:

- For a far more in-depth tutorial on Bash, after the course you may want to check out the Software Carpentry online training materials on the Bash shell. They cover other topics such as pipes and filters (used for chaining multiple commands together and using this powerful technique to manipulate output from previous commands), redirecting input and output from commands from/to files (useful for capturing output), loops for iterating sections of Bash code, and writing Bash scripts to hold multiple commands.

- A handy reference for the most useful Bash shell commands, including others we haven’t seen yet. There are many Bash command “cheat sheets” out there too, which are great as reminders - find one that works for you!

Key Points

The shell is a program that provides access to the operating system’s functions.

A command line interface, like the shell, allows users to type in commands, execute them, and have any output displayed to the user - a cycle that is constantly repeated.

A terminal is an interface or application that lets you interact with the shell.

Navigating a file system using the shell is very similar to using a graphical file viewer.

The working directory is the default location where the shell executes commands.

Use the

lscommand to list files in the working directory.Use the

cdcommand to change the working directory.The behaviour of commands can be altered by passing special arguments - called flags - to them.

Reference to files or directories can be relative to the current working directory (without a leading

/), or absolute (with a leading/).Use the

cpcommand to copy a file.Use the

mvcommand to move a file or directory’s location, and also to rename files.Use the

rmcommand to delete a file. Note that this is a permanent action and cannot be reversed.Use the

mancommand to get help on a command and its arguments and flags.