Jupyter Notebooks as an Integrated Development Environment

Overview

Teaching: 45 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is a Jupyter Notebook and what are the advantages of using one?

How can I analyse example numerical data in Python?

Objectives

Explain the differences between using the Python interpreter and a Jupyter Notebook.

Create a Jupyter Notebook and use it to run Python commands.

Import Python numerical and visualisation libraries.

Read tabular data from a file into a program and visualise that data.

Explain how object state persists within a Notebook.

Save and reload a Notebook.

Export a notebook in PDF format.

Introduction to Jupyter Notebooks

See topic slides.

Launching the Jupyter Notebook Application

Fortunately, Jupyter notebooks are supported by default by the Anaconda distribution. On the command line, we can tell Jupyter to launch its notebook server, which we use to host and manage our notebooks. From within the module01_se_day1-gh-pages/code directory:

jupyter notebook

A local notebook server is launched and a browser is launched to give you access to the application. From this interface, we can create and manage our notebooks.

Our first Notebook

Let’s give you a taste of what’s possible in a Jupyter notebook, and introduce you to some new Python concepts along the way.

We’re going to make use of a couple of Python modules that allow us to analyse and manipulate numerical data, and visualise that data. We’ll be covering these in more detail tomorrow, but:

- NumPy: very popular package for scientific computing. Supports N-dimensional array objects, sophisticated matrix manipulation functions, tools for integrating C/C++ and Fortran code, support for linear algebra, Fourier transforms, and much more.

- matplotlib: 2D plotting library for producing publication quality figures in many formats.

Let’s create a new notebook now. From the notebook server, select New > Python 3. A new notebook will be created (which is saved to the directory from which you ran the notebook server), with a blank initial cell.

Let’s change the title of the notebook to be relevant to what we’re using it for. Select Untitled at the top of the notebook, and enter Inflammation-analysis in the pop-up window, and select Rename.

Anatomy of a Notebook

Jupyter notebooks consist of discussion cells, referred to as markdown cells, and code cells, which contain Python. In markdown cells, we can insert plain text, such as discussions, explanations, etc., which is great for setting the context of what we are doing for the reader. These can be thought of as comments in code, but they’re much more than that - we can apply formatting to these to change appearance, particularly useful for section headings, which allows us to properly structure a notebook with a narrative.

We’ll concentrate on using code cells for now.

Importing the Libraries

To allow us to use the two libraries, we need to first import them into our notebook. On the first line of our notebook, enter the following (don’t type in the line beginning In..., since this just shows us the intended line number in the notebook):

In [1]:

%matplotlib inline

import numpy

from matplotlib import pyplot

The first line is known as a notebook magic, and tells matplotlib that we want its output to be displayed inline, in our case within a notebook, instead of in a separate window. This means our visualisations, as we generate them, will be displayed immediately.

The next two lines tell Python that we want to load each library. The first one tells Python that we want to import (and make use of) the NumPy library, and we’ll refer to this library in our code by using numpy. The second one indicates we want to import a specific module within the matplotlib library called pyplot, which we’ll use to generate our visualisations, and we will refer to this module as pyplot.

When you’ve entered that, press Shift+Enter. This will run this cell in the notebook within Python. If there’s any output, this will be displayed, although in this case there won’t be. You’ll alo notice that the notebook has helpfully given us another cell to enter more things into the notebook.

Load our Example Dataset

We going to use an example dataset based on a clinical trial of inflammation in patients who have been given a new treatment for arthritis. There are a number of these data sets in the data directory, and are each stored in comma-separated values (CSV) format: each row holds information for a single patient, and the columns represent successive days.

We can now use NumPy to load the first dataset into a Python variable. In the next cell, enter:

In [2]:

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='../data/inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

Again, press Shift+Enter to run the cell.

The expression numpy.loadtxt(...) is a function call that asks Python to run the function loadtxt that belongs to the numpy library. We give loadtxt() two arguments: one telling it the CSV file to load, and another telling it that the data on each row is separated by a comma.

Once loaded into the data variable, we can then take a look at the contents of that variable:

In [3]:

print(data)

This time, there is output, which we see displayed directly afterwards in the notebook:

Out [3]:

array([[0., 0., 1., ..., 3., 0., 0.],

[0., 1., 2., ..., 1., 0., 1.],

[0., 1., 1., ..., 2., 1., 1.],

...,

[0., 1., 1., ..., 1., 1., 1.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 2., 0.],

[0., 0., 1., ..., 1., 1., 0.]])

By default, only a few rows and columns are shown (with ... to omit elements when displaying big arrays). To save space, Python displays numbers as 1. instead of 1.0 when there’s nothing interesting after the decimal point.

The data in this case has 60 rows (one for each patient) and 40 columns (one for each day). Each cell in the data represents an inflammation reading on a given day for a patient. So this shows the results of measuring the inflammation of 60 patients over a 40 day period.

Mystery Functions in Notebooks

Is there any easy way to find out what functions NumPy has and how to use them? If you are working in a Jupyter Notebook, you can. If you type the name of something followed by a dot, then you can use tab completion (e.g. type

numpy.and then press tab) to see a list of all functions and attributes that you can use. After selecting one, you can also add a question mark (e.g.numpy.cumprod?), and IPython will return an explanation of the method! This is the same as doinghelp(numpy.cumprod).

Visualising our Example Dataset

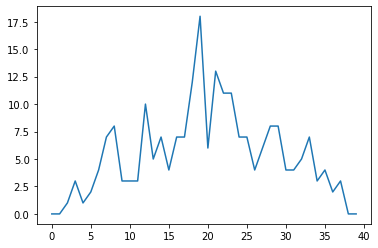

Now we have our inflammation dataset loaded, let’s visualise some of it. Let’s look at the first patient’s data. In the next cell:

In [4]:

inf_plot = pyplot.plot(data[0])

Note that as with lists, NumPy arrays also start at zero. So here, we are looking at just the first row of data, i.e. the first patient.

Here we can see a graph of the first patient’s inflammation over the 40 day period, clearly indicating a trend towards a peak in the middle of the trial, and a trend towards zero inflammation after that. But note we haven’t added any axes, which of course we should! We’ll address this when we look at NumPy in more detail.

But what’s interesting is that we’ve used a notebook to very quickly visualise part of our data.

A Warning about Object State

When I type code in the notebook, the objects live in memory between cells. So far, we’ve entered Python into each cell in order, and each cell has been evaluated in order. But we can also change cell contents and re-evaluate them.

If we go back and edit cell [3] to the following to change the data points on day 11 for our first patient:

In [3]:

data[0][10] = 8.0

But we haven’t re-evaluated that cell yet, so it’s important to note that the notebook is now in an inconsistent state: the following cells have not taken this change into account. So we have to be careful!

Let’s go ahead and press Shift+Enter to re-evaluate that cell and change our dataset.

Since the Python we entered doesn’t output anything, we see the output from that cell disappears. We can also see that the number for that cell changes to [4]. This indicates that it’s the 4th cell evaluated in our notebook (replacing the previous 2nd cell).

But the following graph is still showing an old value for the 10th day. We could re-evaluate this cell too, but if we had many other cells, it would be tiresome to re-evaluate them all.

The thing to remember is that cells are not always evaluated in order - it depends on how we change and evaluate our notebook.

To ensure we have a our notebook in a consistent state, we can re-evaluate all cells in the entire notebook by selecting the >> icon. We can now see that our graph displays the correct value for day 10.

A More Explicit Example of Object State

If I set a variable in a notebook:

number = 0And then in the next cell enter:

number = number + 1 print(number)We’ll get:

1However, if we constantly re-evaluate the second cell, the number will continue to increment. So it’s important to remember that if you move your cursor around in the notebook and change things, it doesn’t always run top to bottom.

Saving and Reloading a Notebook

We can also save the state of a notebook and reload it later. If you select File > Save as..., leave the directory option blank, then select Save, the notebook will be saved in the directory where you started the Jupyter notebook.

Exporting a Notebook to Another Format

You also have the option to export your notebook and save it in a different format. There are many formats, but include Python scripts and PDF.

To export a Python version of your notebook, go to File > Download as > Python (.py). This will download the notebook as a Python script you can run as a standalone program.

Key Points

A Juptyer Notebook is a type of Integrated Development Environment, or IDE.

Launch the Jupyter application using

jupyter notebookfrom the command line.The Python interpreter always runs commands sequentially, whilst a Notebook runs each ‘cell’ of commands in the order in which the user processes them.

Import a library into a Python script using

import libraryname.Use

numpy.loadtxt()to load in numerical tabular data into Python.Use the

pyplotlibrary frommatplotlibto create a simple visualization of data.Use the Jupyter Notebook menu to save and export Notebooks to local storage.

Use the Jupyter application menu to reload Notebooks from local storage.