Containers

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How can I store many values together?

Objectives

Explain what lists, tuples, sets, and dictionaries are, and their key differences.

Create, populate, and retrieve values from lists and other containers.

Reorder and slice list elements.

Change the values of individual container elements where supported.

Select individual values and subsections from containers.

Container types are those that can hold other objects. Let’s create a new Jupyter notebook to explore containers, as well as provide an active record of what we’ve done. Select New > Python 3 from the Jupyter server menu, and name the notebook Containers.

Lists

One of the most fundamental data structures in any language is the array, used to hold many values at once. Python doesn’t have a native array data structure, but it has the list which is much more general and can be used as a multidimensional array quite easily. You’ll likely find, for general purposes, you’ll be using lists a lot. How you use them also forms the basis for how you use more specialised types of containers we’ll see later.

Creating and Extracting Things from Lists

To define a list we simply write a comma separated list of items in square brackets:

odds = [1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 15]

more_numbers = [ [1, 2], [3, 4, 5], [ [6, 7], [8] ] ]

We can see that our multi-dimensional array can contain elements themselves of any size and depth. This could be used as way of representing matrices, but later we’ll learn a better way to represent these.

A list in Python is just an ordered collection of items which can be of any type. By comparison, in most languages an array is an ordered collection of items of a single type - so a list is more flexible than an array.

various_things = [1, 2, 'banana', 3.4, [1, 2] ]

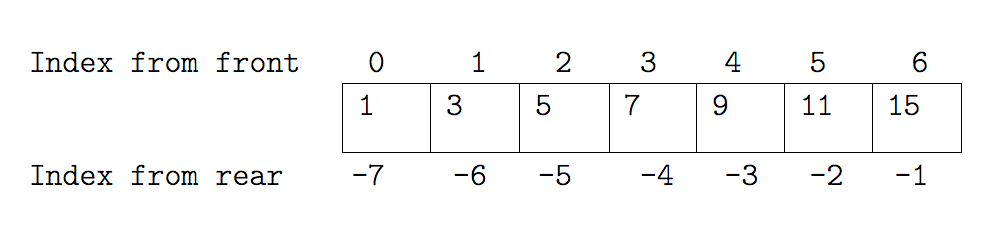

We can select individual elements from lists by indexing them. Looking at our odds list:

For example:

print(odds[0], odds[-1])

This will print the first and last elements of a list:

1 15

We can replace elements within a specific part of the list (note that in Python, indexes start at 0):

odds[6] = 13

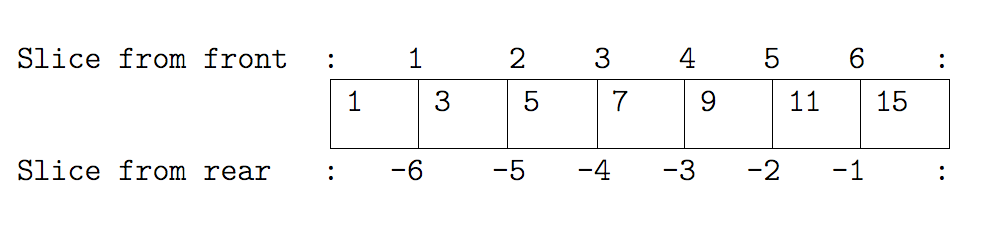

We can also slice lists to either extract or set an arbitrary subset of the list.

Note that here, we are selecting the boundaries between elements, and not the indexes.

For example, to show us elements 3 to 5 (inclusive) in our list:

odds[2:5]

We select the boundaries 2 and 5, which produce:

[5, 7, 9]

We can also leave out either start or end parts and they will assume their maximum possible value:

odds[5:]

[11, 13]

Or even:

odds[:]

Which will show us the whole list.

[1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13]

Slicing From the End

Use slicing to access only the last four characters of a string or entries of a list.

string_for_slicing = "Observation date: 02-Feb-2013" list_for_slicing = [["fluorine", "F"], ["chlorine", "Cl"], ["bromine", "Br"], ["iodine", "I"], ["astatine", "At"]]"2013" [["chlorine", "Cl"], ["bromine", "Br"], ["iodine", "I"], ["astatine", "At"]]Would your solution work regardless of whether you knew beforehand the length of the string or list (e.g. if you wanted to apply the solution to a set of lists of different lengths)? If not, try to change your approach to make it more robust.

Hint: Remember that indices can be negative as well as positive

Solution

Use negative indices to count elements from the end of a container (such as list or string):

string_for_slicing[-4:] list_for_slicing[-4:]

Strings as Containers

Conceptually, a string is a type of container, in this case of letters. We can also index and slice strings in the same way as a list:

element = 'oxygen'

print(element[1], element[0:3], element[3:6])

oxy gen

Only One Way to do It

Which demonstrates a key design principle behind Python: “there should be one - and preferably only one - obvious way to do it.” “To describe something as ‘clever’ is not considered a compliment in Python culture.” - Alex Martelli, Python Software Foundation Fellow.

But since strings are immutable types, we cannot change elements ‘in place’:

element[2] = 'y'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

Sometimes it’s useful to be able to split a string by a delimiter into a list:

str = 'This is a string'

a_list = str.split()

print(a_list)

['This', 'is', 'a', 'string']

We can also join together a list of strings into a single string:

new_str = ' '.join(a_list)

print(new_str)

This is a string

Adding and Deleting Elements

We can also add and delete elements from a Python list at any time:

odds.append(21)

del odds[0]

odds

Which will show us the list with a ‘21’ added to the end and its first element removed:

[3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 21]

Checking an Elements are in a List

We can also check if an element is within a list:

9 in odds

True

Tuples

A tuple is an immutable sequence. It is like a list, in terms of indexing, repetition and nested objects, except it cannot be changed - it’s an immutable type. Instead of using square brackets to define them, we use round brackets.

With a single element tuple, you need to end the assignment with a comma.

x = 0,

y = ('Apple', 'Banana', 'Cherry')

type(x)

<class 'tuple'>

So similarly to lists for indexing elements:

y[1]

'Banana'

But as we mentioned, it’s an immutable type:

my_tuple = ('Hello', 'World')

my_tuple[0] = 'Goodbye'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

Sets

A Python set is equivalent to a set in mathematics. It may contain many values of different types, as long as they are immutable (e.g. integers, strings, floats, tuples), but is strictly unordered. Indeed, set elements are usually not stored in the order they appear within a set, which enables Python to do faster checking whether an element is in a set.

x = {1, 2}

y = {1, 2, 1}

print(x == y)

Since x and y are equal sets, we get:

True

We can also add and remove set elements:

x.remove(2)

x.add(3)

print(x)

Note that the remove and add methods change x directly:

{1, 3}

As you may expect, you can also perform standard set operations on sets. For union:

a = {4, 5, 6}

b = {6, 7, 8}

a.union(b)

{4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

We can also do intersection:

a.intersection(b)

{6}

And difference:

a.difference(b)

{4, 5}

You can also do other useful operations on sets, such as removing elements of one set from another, if one is a subset or superset of another, and so on.

Mutability

An important thing to remember is that Python variables are simply references to values, and also that they fall into two distinct types:

- Immutable types: value changes by referencing a newly created value, e.g. when changing a letter in a string

- Mutable types: values can be changed ‘in place’, e.g. changing or adding an item in a list

This matters when you are ‘copying’ variables or passing them as arguments to functions.

Dictionaries

Python supports a container type called a dictionary.

This is also known as an “associative array”, “map” or “hash” in other languages.

In a list, we use a number to look up an element:

names = 'Martin Luther King'.split(' ')

names[1]

'Luther'

In a dictionary, we look up an element using another object of our choice:

me = { 'name': 'Joe', 'age': 39,

'Jobs': ['Programmer', 'Teacher'] }

me

{'Jobs': ['Programmer', 'Teacher'], 'age': 39, 'name': 'Joe'}

me['Jobs']

['Programmer', 'Teacher']

me['age']

39

type(me)

<class 'dict'>

Keys and Values

The things we can use to look up with are called keys:

me.keys()

dict_keys(['age', 'Jobs', 'name'])

The things we can look up are called values:

me.values()

dict_values([39, ['Programmer', 'Teacher'], 'Joe'])

When we test for containment on a dict we test on the keys:

'Jobs' in me

True

'Joe' in me

False

'Joe' in me.values()

True

Immutable Keys Only

The way in which dictionaries work is one of the coolest things in computer science: the “hash table”. The details of this are beyond the scope of this course, but we will consider some aspects in the section on performance programming.

One consequence of this implementation is that you can only use immutable things as keys.

good_match = {

("Lamb", "Mint"): True,

("Bacon", "Chocolate"): False

}

But:

illegal = {

["Lamb", "Mint"]: True,

["Bacon", "Chocolate"]: False

}

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 3, in <module>

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'

Remember – square brackets denote lists, round brackets denote tuples.

No Guarantee of Order

Another consequence of the way dictionaries work is that there’s no guaranteed order among the elements:

my_dict = {'0': 0, '1':1, '2': 2, '3': 3, '4': 4}

print(my_dict)

print(my_dict.values())

{'2': 2, '1': 1, '0': 0, '3': 3, '4': 4}

dict_values([2, 1, 0, 3, 4])

Beware ‘Copying’ of Containers!

Here, note that y is not equal to the contents of x, it is a second label on the same object. So when we change y, we are also changing x. This is generally true for mutable types in Python.

x = [1, 2, 3]

y = x[:]

y[1] = 20

print(x, y)

[1, 2, 3] [1, 20, 3]

In this case, we are using x[:] to create a new list containing all the elements of x which is assigned to y. This happens whenever we take any sized slice from a list.

This gets more complicated when we consider nested lists.

x = [['a', 'b'] , 'c']

y = x

z = x[:]

x[0][1] = 'd'

z[1] = 'e'

print(x, y, z)

[['a', 'd'], 'c'] [['a', 'd'], 'c'] [['a', 'd'], 'e']

Note that x and y are the same as we may not expect. But z, despite being a copy of x, now contains 'd' in its nested list.

The copies that we make through slicing are called shallow copies: we don’t copy all the objects they contain, only the references to them. This is why the nested list in x[0] is not copied, so z[0] still refers to it. It is possible to actually create copies of all the contents, however deeply nested they are - this is called a deep copy. Python provides methods for that in its standard library in the copy module.

General Rule

Your programs will be faster and more readable if you use the appropriate container type for your data’s meaning. Always use a set for lists which can’t in principle contain the same data twice, always use a dictionary for anything which feels like a mapping from keys to values.

Key Points

Python containers can contain values of any type.

Lists, sets, and dictionaries are mutable types whose values can be changed after creation.

Lists store elements as an ordered sequence of potentially non-unique values.

Dictionaries store elements as unordered key-value pairs.

Dictionary keys are required to be of an immutable type.

Sets are an unordered collection of unique elements.

Containers can contain other containers as elements.

Use

x[a:b]to extract a subset of data fromx, withaandbrepresenting element boundaries, not indexes.Tuples are an immutable type whose values cannot be changed after creation and must be re-created.

Doing

x = y, whereyis a container, doesn’t copy its elements, it just creates a new reference to it.