Scientific Visualisation with Matplotlib

Overview

Teaching: 50 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

How can I visualise my data?

Objectives

Generate a heatmap of longitudinal, numerical tabular data.

Create graphs of mean, minimum, and maximum characteristics over time from data.

Create graphs showing multiple data characteristics within a single plot and separate plots.

Save a generated graph to local storage.

Write a script to visualise data from multiple data files.

Use a library function to get a list of filenames that match a certain pattern.

The mathematician Richard Hamming once said, “The purpose of computing is insight, not numbers,” and

the best way to develop insight is often to visualize data. Visualization deserves an entire

lecture of its own, but we can explore a few features of Python’s matplotlib library here. While

there is no official plotting library, matplotlib is the de facto standard.

Some IPython Magic

As we did yesterday, when using a Jupyter notebook you’ll need to use the following magic in order for your matplotlib images to appear in the notebook when

show()is called:%matplotlib inlineAgain, note that you only have to execute this function once per notebook.

Lines beginning with a single percent are not python code: they control how the notebook deals with python code. Lines beginning with two percents are “cell magics”, that tell Jupyter notebook how to interpret the particular cell.

Visualising our Inflammation Data

First, we will import the pyplot module from matplotlib and use two of its functions to create and display a heat map of our data (you won’t need the line beginning data = if you’re continuing directly after the previous lesson and already have it loaded):

import matplotlib.pyplot

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='../data/inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

image = matplotlib.pyplot.imshow(data)

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Blue pixels in this heat map represent low values, while yellow pixels represent high values. As we can see, inflammation rises and falls over a 40-day period.

Let’s take a look at the average inflammation over time:

ave_inflammation = numpy.mean(data, axis=0)

ave_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(ave_inflammation)

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Here, we have put the average per day across all patients in the variable ave_inflammation, then asked matplotlib.pyplot to create and display a line graph of those values. The result is a roughly linear rise and fall, which is suspicious: we might instead expect a sharper rise and slower fall. Let’s have a look at two other statistics:

max_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

min_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

The maximum value rises and falls smoothly, while the minimum seems to be a step function. Neither trend seems particularly likely, so either there’s a mistake in our calculations or something is wrong with our data. This insight would have been difficult to reach by examining the numbers themselves without visualization tools.

Make Your Own Plot

Create a plot showing the standard deviation (using

numpy.std) of the inflammation data for each day across all patients.Solution

std_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.std(data, axis=0)) matplotlib.pyplot.show()

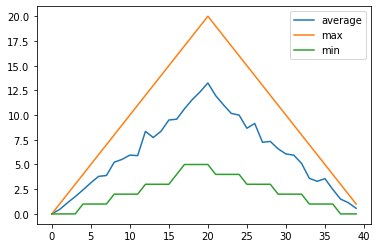

Multiple Plots: Single Graph

Perhaps we want to compare the minimum, maximum, and average plots overlayed together. This would allow us to see the range of values across each day in the trial. Let’s use PyCharm to build a script called overlay_graphs.py that positions our three graphs in a single plot, or ‘figure’.

So Matplotlib divides a figure object up into axes: each pair of axes is one ‘subplot’. To make a boring figure with just one pair of axes, however, we can just ask for a default new figure, with brand new axes. The subplots() function returns a (figure, axis) pair, which we can deal out with parallel assignment.

Given we have a stacked set of graphs in a single figure, we use legend() on our axes to add one which uses our given plot labels.

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='../data/inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

all_graphs, all_graphs_axes = matplotlib.pyplot.subplots()

all_graphs_axes.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0), label='average')

all_graphs_axes.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0), label='max')

all_graphs_axes.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0), label='min')

all_graphs_axes.legend()

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

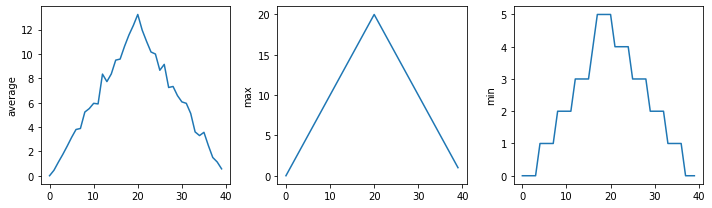

Multiple Plots: Multiple Graphs

We can also group similar plots within a single figure using subplots next to each other within that figure. Let’s use PyCharm to build another script called multiple_graphs.py that positions our three graphs side-by-side and introduces a number of new commands.

The function matplotlib.pyplot.figure() creates a space into which we will place all of our plots. The parameter figsize tells Python how big to make this space.

Each subplot is placed into the figure using its add_subplot method. The add_subplot method takes 3 parameters. The first denotes how many total rows of subplots there are, the second parameter refers to the total number of subplot columns, and the final parameter denotes which subplot your variable is referencing (left-to-right, top-to-bottom).

Each subplot is stored in a different variable (axes1, axes2, axes3). Once a subplot is created, the axes can be titled using the set_xlabel() command (or set_ylabel()).

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='../data/inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

avg_axes = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1)

max_axes = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2)

min_axes = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3)

avg_axes.set_ylabel('average')

avg_axes.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0))

max_axes.set_ylabel('max')

max_axes.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

min_axes.set_ylabel('min')

min_axes.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

The call to loadtxt reads our data, and the rest of the program tells the plotting library how large we want the figure to be, that we’re creating three subplots, what to draw for each one, and that we want a tight layout. (If we leave out that call to fig.tight_layout(), the graphs will actually be squeezed together more closely.)

Moving Plots Around

Save a new version of the program which displays the three plots vertically instead of horizontally.

Solution

import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='../data/inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',') # change figsize (swap width and height) fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(3.0, 10.0)) # change add_subplot (swap first two parameters) avg_axes = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 1) max_axes = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 2) min_axes = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 3) avg_axes.set_ylabel('average') avg_axes.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0)) max_axes.set_ylabel('max') max_axes.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0)) min_axes.set_ylabel('min') min_axes.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) fig.tight_layout() matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Saving our Plots

We can also save our plots to disk. Let’s change our overlay_graphs.py script to do that, by adding the following just before we call matplotlib.pyplot.show():

all_graphs.savefig('overlay_graphs.png')

When we re-run the script, you should see a new overlay_graphs.png file in the same directory as the script.

Dealing with Multiple Datasets

We also have other inflammation datasets, located in the data directory. Let’s try to generate and save visualisations for each of these datasets so we can compare them against each other, to increase our confidence that we have sensible datasets.

First, we need to have a way of determining a list of all our inflammation data files. Their filenames all follow the pattern inflammation-XX.csv, where XX refers to the number of that dataset. We can use the glob library here to help us get these filenames.

The glob library contains a function, also called glob, that finds files and directories whose names match a pattern. We provide those patterns as strings: the character * matches zero or more characters, while ? matches any one character. We can use this to get the names of all the CSV files in the data directory which resides in the directory above like so:

import glob

filenames = sorted(glob.glob('inflammation*.csv'))

print(filenames)

Now, glob() returns a list of matching filenames (and directory paths) in arbitrary order, so we use the inbuilt sorted() Python function to sort this for us:

['../data/inflammation-01.csv', '../data/inflammation-02.csv', '../data/inflammation-03.csv', '../data/inflammation-04.csv', '../data/inflammation-05.csv', '../data/inflammation-06.csv', '../data/inflammation-07.csv', '../data/inflammation-08.csv', '../data/inflammation-09.csv', '../data/inflammation-10.csv', '../data/inflammation-11.csv', '../data/inflammation-12.csv']

This means we can loop over it to do something with each filename in turn.

We’d like to save each of the generated plots using the pattern inflammation-XX.png. Each of the filenames we have in filenames has a .csv. on the end. So how to go about replacing the file extension with a .png one? We can use the os library to extract the file path for us, e.g.

import os

filename = '../data/inflammation-01.csv'

base = os.path.splitext(filename)[0]

new_filename = base + '.png'

print(new_filename)

os.path.splitext() splits a filename into its path/filename, and file extension components. So we just append the .png extension to the path/filename part, and get:

'../data/inflammation-01.png'

Processing Multiple Inflammation Datasets

Modify our script that generates the three horizontal graphs in a single figure (

multiple_graphs.py) so that it processes each of the inflammation datasets in turn (each with a filename of the forminflammation-XX.csv), generating the figure for each, and saving it to local disk as a PNG file with a filename of the forminflammation-XX.png.Solution

import glob import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot filenames = sorted(glob.glob('../data/inflammation*.csv')) for f in filenames: data = numpy.loadtxt(fname=f, delimiter=',') fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0)) avg_axes = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1) max_axes = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2) min_axes = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3) avg_axes.set_ylabel('average') avg_axes.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0)) max_axes.set_ylabel('max') max_axes.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0)) min_axes.set_ylabel('min') min_axes.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) fig.tight_layout() fig.savefig(f + '.png')Refactor your graph generation code within a new function named

generate_graph()that takes a NumPy array as an argument, generates the figure from the input data, and returns the generated figure. Use this function within your loop instead.Solution

import glob import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot def generate_graph(data): fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0)) avg_axes = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1) max_axes = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2) min_axes = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3) avg_axes.set_ylabel('average') avg_axes.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0)) max_axes.set_ylabel('max') max_axes.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0)) min_axes.set_ylabel('min') min_axes.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) fig.tight_layout() return fig filenames = sorted(glob.glob('../data/inflammation*.csv')) for f in filenames: data = numpy.loadtxt(fname=f, delimiter=',') figure = generate_graph(data) figure.savefig(f + '.png')

Key Points

Use

%matplotlib inlineto show our graphs immediately after creation within a Notebook.Use

matplotlib.pyplot.plot(data)to generate a graph fromdata.Use

matplotlib.pyplot.show()to display a generated graph.Matplotlib allows us to add multiple graphs within a single plot, or within separate plots using a

figure.Set vertical axes labels using

set_ylabel('label').Save a generated graph using

graph.savefig('filename').Use

glob.glob(pattern)to create a list of files whose names match a pattern.Use

*in a pattern to match zero or more characters, and?to match any single character.